Economic Causes of Fragmented Industries

Industries are fragmented for various reasons, with vastly differing implications for competing in them. Some industries are fragmented for historical reasons — because of the resources or abilities of the firms historically in them — and there is no fundamental economic basis for fragmentation. However, in many industries there are underlying economic causes and the principal ones seem to be as follows:

Table of Content

- 1 Economic Causes of Fragmented Industries

- 1.1 Low overall Entry Barriers

- 1.2 Absence of Economies of Scale or Experience Curve

- 1.3 High Transportation Cost

- 1.4 High Inventory Costs or Erratic Sales Fluctuations

- 1.5 No Advantages of Size in Dealing with Buyers or Suppliers

- 1.6 Diseconomies of Scale in Some Important Aspects

- 1.7 Direct Market Needs

- 1.8 High Product Differentiation, Particularly if Based on Image

- 1.9 Exit Barriers

- 1.10 Basic approach to overcoming fragmentation

- 1.11 Make Acquisitions for a Critical Mass

- 1.12 Recognize Industry Trends Early

- 2 Consolidation

Low overall Entry Barriers

Nearly all fragmented industries have low overall entry barriers. Otherwise, they could not be populated by so many small firms. However, although a prerequisite to fragmentation, low entry barriers are usually insufficient to explain it. Fragmentation is nearly always accompanied by one or more of the other causes discussed below.

Absence of Economies of Scale or Experience Curve

Most fragmented industries are characterized by the absence of significant scale economies or learning curves in any major aspect of the business, whether it be manufacturing processes characterized by few if any economies of scale or experiencing cost declines because the process is a simple fabrication or assembly operation (fiberglass and polyurethane molding), is a straightforward warehousing operation (electronic component distribution), has an inherently high labor content (security guards), has a high personal service content or is intrinsically hard to mechanize or routinize.

High Transportation Cost

High transportation costs limit the size of an efficient plant or production location despite the presence of economies of scale. Transportation costs balanced against economies of scale determine the radius a plant can economically service. Transportation costs are high in such industries as cement, fluid milk, and highly caustic chemicals. They are effectively high in many service industries because the service is “produced” at the customer’s premises or the customer must come to where the service is produced.

High Inventory Costs or Erratic Sales Fluctuations

Although there may be intrinsic economies of scale in the production process, they may not be reaped if inventory carrying costs are high and sales fluctuate. Here production has to be built up and down, which works against the construction of large-scale, capital-intensive facilities and operating them continuously.

Similarly, if sales are very erratic and fluctuate over a wide range, then the firm with large-scale facilities may not have advantages over the smaller, more nimble firm, even if the large firm’s production operations are more efficient in a fully loaded state. Small-scale, less specialized facilities or distribution systems are usually more flexible in absorbing output shifts than large, more specialized ones, even though they may have higher operating costs at a steady operating rate.

No Advantages of Size in Dealing with Buyers or Suppliers

The structure of the buyer groups and supplier industries is such that a firm gains no significant bargaining power in dealing with this adjacent business from being large. Buyers, for example, might be so large that even a large firm in the industry would only be marginally better off in bargaining with them than a smaller firm. Sometimes powerful buyers or suppliers will be powerful enough to keep companies in the industry small, by intentionally spreading their business or encouraging entry.

Diseconomies of Scale in Some Important Aspects

Diseconomies of scale can stem from a variety of factors. Rapid product changes or style changes demand quick response and intense coordination among functions. Where frequent introductions and style changes are essential to competition, allowing only short lead times, a large firm may be less efficient than a smaller one – which seems to be true in women’s clothing and other industries in which style plays a major role in the competition.

If maintaining a low overhead is crucial to success, this factor can favor the small firm under the iron hand of an owner-manager, unencumbered by pension plans and other corporate trappings and less subject to scrutiny by government regulators than the large firm. A highly diverse product line requiring customization to individual users requires a great deal of user-manufacturer interface on small volumes of product and can favor the small firm over the larger one.

The business forms industry may be an example of one in which such product diversity has led to fragmentation. Although there are exceptions, if heavy creative content is required, it is often difficult to maintain the productivity of creative personnel in a very large company. One sees no dominant firms in industries such as advertising and interior design.

If close local control and supervision of operations is essential to success the small firm may have an edge. In some industries, particularly services like nightclubs and eating places, an intense amount of close, personal supervision seems to be required. Absentee management works less effectively in such business, as a general rule than an owner-manager who maintains close control over a relatively small operation.

Smaller firms are often more efficient where personal service is the key to the business. The quality of personal service and the customer’s perception that individualized, responsive service is being provided often seem to decline with the size of the firm once a threshold is reached. This factor seems to lead to fragmentation in such industries as beauty care and consulting.

Where a local image and local contacts often are keys to the business the large firm can be at a disadvantage. In some industries like aluminium fabricating, building supply, and many distribution businesses, a local presence is essential to success. Intense business development, contact building, and sales effort on a local level are necessary to compete. In such industries, a local or regional firm can often outperform a larger firm provided it faces no significant cost disadvantages.

Direct Market Needs

In some industries buyers’ tastes are fragmented, with different buyers each desiring special varieties of a product and willing (and able) to pay a premium for it rather than accept a more standardized version. Thus the demand for any particular product variety is small, and adequate volume is not present to support production, distribution, or marketing strategies that would yield advantages to the large firm.

Sometimes fragmented buyers’ tastes stem from regional or local differences in market needs, for example, in the fire engine industry. Every local fire department wants its customized fire engine with many expensive bells, whistles, and other options. Nearly every fire engine sold is unique. Production is a job shop and almost purely assembly, and there are dozens of fire engine manufacturers, none of whom has a major market share.

High Product Differentiation, Particularly if Based on Image

If product differentiation is very high based on image, it can place limits on a firm’s size and provide an umbrella that allows inefficient firms to survive. Large size may be inconsistent with an image of exclusivity or with the buyer’s desire to have a brand all his or her own.

Closely related to this situation is one in which key suppliers to the industry value exclusively a particular image in the channel for their products or services. Performing artists, for example, may prefer dealing with a small booking agency or record label that carries the image they desire to cultivate.

Exit Barriers

If there are exit barriers, marginal firms will tend to stay in the industry and thereby hold back consolidation. Aside from economic exit barriers, managerial exit barriers appear to be common in fragmented industries. There may be competitors with goals that are not necessarily profit-oriented.

Certain businesses may have a romantic appeal or excitement that attracts competitors who want to be in the industry despite low or even nonexistent profitability. This factor seems to be common in such industries as fishing and talent agencies.

Basic approach to overcoming fragmentation

It recognizes that the root cause of the fragmentation cannot be altered. Rather, the strategy is to neutralize the parts of the business subject to fragmentation to allow advantages of sharing in other aspects to come into play.

Make Acquisitions for a Critical Mass

In some industries, there may ultimately be some advantages to holding a significant share, but it is extremely difficult to build a share incrementally because of the causes of fragmentation. For example, if local contacts are important in selling, it is difficult to invade the territory of other firms to expand. But if the firm can develop a threshold share, it can begin to reap any significant advantages of scale. Companies can be successful, provided the acquisitions can be integrated and managed.

Recognize Industry Trends Early

Sometimes industries consolidate naturally as they mature, particularly if the primary source of fragmentation was the newness of the industry; or exogenous industry trends can lead to consolidation by altering the causes of fragmentation.

Example: Computer service bureaus are facing increasing competition from minicomputers and microcomputers. This new technology means that even small and medium-sized firms can afford to have their computer. Thus, service bureaus increasingly have had to service the large, multilocation company to continue their growth and/or to offer sophisticated programming and other services in addition to just computer time. This development has increased the economies of scale in the service bureau industry and is leading to consolidation.

In the service bureau example, the threat of substitute products triggered consolidation by shifting buyers’ needs thereby stimulating service changes that were increasingly subject to economies of scale. In other industries, changes in buyers’ tastes, changes in the structure of distribution channels, and innumerable other industry trends may operate, directly or indirectly, on the causes of fragmentation.

Government or regulatory changes can force consolidation by raising standards in the product or manufacturing process beyond the reach of small firms through the creation of economies of scale. Recognizing the ultimate effect of such trends, and positioning the company to take advantage of them, can be an important way of overcoming fragmentation.

Consolidation

Consolidation has long been used to achieve and sustain power in the marketplace. Indeed, creating a monopoly position through consolidation can be one of the most effective ways of achieving economic returns through a business venture. This long history does not imply, however, that consolidation strategies have remained the same. Using historical documentation and an analysis of current merger and acquisition activity, we show how consolidation strategies have evolved through the past century, and how they could be improved using a more rigorous framework.

As with the prior waves, consolidation is ultimately encouraged by changes in the external environment, and many factors align to drive the current boom. However, the current wave of consolidation is much broader, spanning industrial and service industries. In addition, specialized financial players have joined the traditional consolidators, resulting in even greater market activity.

We certainly recognize that success for a consolidation play relies significantly on implementation. Our 5 C’s may suggest that an industry is ripe for a consolidation play only to have the consolidator fail during implementation. Conversely, our framework may suggest that successful consolidation is unlikely but a superior consolidator could overcome the negative issues.

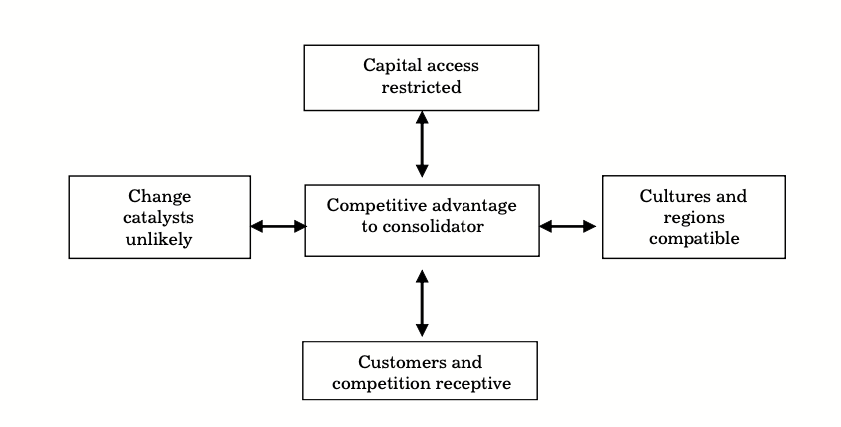

The framework is meant to guide thinking about consolidations and highlight the factors that will ultimately influence success. As depicted the 5 C’s are Capital access restricted; Cultures and regions compatible; Customers and competitors receptive; Change catalysts unlikely; and Competitive advantage realizable for the consolidator. Each element of the framework will be detailed further in the following sections, but we first present a quick note on the interaction between the variables. The outer four variables address the major industry issues and highlight potential pitfalls. They are focused on the industry as a whole and should apply somewhat uniformly across individual businesses.

They should be examined by asking: “Is this issue significant in this industry?” If the answer is affirmative, then consolidation may well be successful. However, the fifth and center variable is more business specific and should be examined by asking: “Do these opportunities exist and are they realizable?” Essentially, the ultimate success in a consolidation play relies upon the proper implementation of the fifth variable.

Underlying this analysis must be the broader question: “Why is this industry fragmented now and what has changed to make consolidation possible?” According to Michael Porter in Competitive Strategy, industries are usually fragmented for five general reasons. These reasons will be addressed in turn as they pertain to each of our 5 C’s but it is useful to summarise them here. They are:

- Low entry barriers and/or high exit barriers

- Lack of power advantages with buyers and/or suppliers

- No economies of scale or scope

- Regional issues: high transport costs, high inventory costs, or diverse markets

- Regulatory issues

Porter’s 5 C Model

There is some obvious overlap with some of our 5 C’s. Porter’s reasons are a useful starting point for understanding industry fragmentation but fail to fully cover all potential issues of a consolidation strategy. We highlight his work because it provides a useful foundation upon which to examine a consolidation play using the 5 C’s. In the following sections, we will address each of the 5 C’s in turn and incorporate the issues that Porter raises into our discussion.

Capital Access Enhanced

Fragmented industries are populated with businesses that are almost by definition small, private companies. As such, these businesses may face a more expensive cost of capital than they could get from the public markets. Thus, growth and capital reinvestment in these small businesses are limited or at least costly, which explains the evolution of the fragmented industry.

To invest and grow, the businesses would either have enough size to go public or find more favorable private capital. Either way, obtaining a cheaper cost of capital may create an advantage within the industry and allow for growth. This is the attractiveness for consolidators of industries with restricted capital access. A consolidated firm will not face such high transaction and information costs in the capital markets because of the economies of scale it will enjoy. However, industries with few capital requirements and no need for growth may not necessarily need cheaper capital.

Thus, to determine if this variable is both significant within the industry and suggests that industry consolidation will be successful, we need to ask several questions:

- Do industry players face a high cost of capital that would be cheaper in a consolidated firm?

- Is capital a significant enough factor in the industry that cheaper capital would create a significant competitive advantage?

- Will the capital markets support a consolidation play in this industry?

If the answer is affirmative to all three, then this variable suggests that industry consolidation will be successful. While most industries will suggest an affirmative answer to the first two questions, there may be few industries where cheaper capital is somewhat irrelevant.

Example: The beauty salon industry has few capital requirements and is certainly fragmented. Many, if not all, salons are privately owned by small business owners. The industry is near saturation in most markets and thus, there are few growth opportunities. The retail channels are evolving into the shopping malls but for the most part, capital requirements remain small. Thus, restricted capital access is not a major concern.

There may also be an example of a fragmented industry that enjoys cheap capital that could not gain even cheaper capital for a consolidated firm.

The final question is perhaps the most basic but also the most important. Currently, the capital markets are strong and willing to support consolidation plays. An economic downturn will sour the market appetite for such plays and could spell disaster for a consolidated firm.

Cultures and Regions Compatible

Fragmented industries develop for a variety of reasons. These vary from market segments that require specialized businesses and products to the historical evolution of the industry. Using Porter’s work, low barriers to entry and lack of a power advantage over buyers and/or suppliers may account for the historical development of fragmentation of this industry. Porter also highlights regional issues, such as high transportation costs, as a reason for industry fragmentation. Another potential reason for industry fragmentation may simply be the personalities of the firm owners, who want to run their businesses.

The fundamental outcome of all of these factors is that the cultures and regions of the individual businesses may be very different. Cultural issues can be further subdivided into both regional and industrial differences. Regional cultures may seem relatively straightforward but are often subtle and can be often overlooked.

Industry cultures include not only the personalities of the operators in the industry but also the personalities and norms of the various individuals and organizations that interact with the industry. Finally, the industry may dictate a need for distinct regional operations that may hinder a consolidator’s ability to create competitive advantages.

Consolidators rarely mention this variable. Unfortunately, we suspect it is also one of the primary reasons for consolidation failure. Many times, these issues are downplayed or worse, overlooked. They emerge during implementation and may quickly sabotage other successes. An honest appraisal of the feasibility of consolidation among business cultures and across regions is essential.

One must ask the following questions:

- Are there distinct cultures present within the industry and the individual businesses?

- Is there no economic reason for distinct regional orientation?

- Are the cultures and regions realistically compatible across businesses?

An affirmative answer to all three suggests that industry consolidation will succeed. However, assessing compatibility is extremely difficult, primarily because fully identifying and analyzing cultures is so difficult. The auto service and home contracting industries have historically been attractive areas for a consolidation play. However, the culture of the businesses and the workers in such industries does not lend itself to compatibility.

In the home contracting business, workers operate as individual sub-contractors, generally responsible to themselves only. Home contractors face a continual management challenge to meet deadlines and budgets in the face of all these individuals. Consolidation of such an industry would require a break in the paradigm with which the workers have grown comfortable.

Example: The Fortress Group in Washington, DC is attempting to consolidate home building. (Mayer, 1997; Comer, 1997) Their primary obstacle (the main focus of the criticism against them) is that they will be unable to integrate the numerous independent operators into a unified business team.

There are several other examples of industries where consolidation has failed due to cultural and regional issues.

Example: The Foster Management Group attempted an unsuccessful consolidation in mental healthcare. Despite the economic benefits of consolidation, the primary roadblock to success was that the psychiatrists were unwilling to give up their autonomy to a large organization.

Finally, the dental industry might, at first, seem like a potential consolidation play. However, many people probably enter dentistry as an opportunity to become small business owners. They are less attracted to the actual work of being a dentist. As such, they are unlikely to be receptive to a consolidation play that will strip away their ability to manage their own business.

Customers and Competitors Receptive

The historical evolution of fragmented industries has affected customers and competitors. As Porter would assert, there has likely been little, if any, power advantage over buyers and suppliers. Both the customers of the industry and the competitors within the industry are likely to be comfortable with their expectations. A consolidator entering the industry is likely to rock the boat and thus, the effect needs to be examined closely.

This variable contains several deeper issues as well. With the customers, issues of branding and customer perception and acceptance are relevant. With competitors, issues of response tactics and willingness to be consolidated arise. All issues fundamentally rest on the goal of successfully ascertaining the overall market response to a consolidation play. The following general questions should be addressed:

- Is this a relatively static industry with set expectations among all participants?

- Will customers perceive a consolidator negatively?

- Are competitors likely to fight at every turn along multiple fronts?

An affirmative answer to all three suggests that a consolidator will face stiff opposition and may not be able to successfully consolidate the industry. In the funeral home industry, for example, the answers to the first two are affirmative. Customers are accustomed to family-owned funeral parlors that are members of the community. A national funeral parlor chain would certainly face negative customer perceptions.

A consolidator looking to exploit economies of scale by performing embalming services at a central assembly-line style facility would not be well received. These issues can be resolved, but they must be recognized and addressed early. Service Corporation International has been able to consolidate funeral homes by preserving the compassionate front to the customer despite leveraging economies of scale.

Another example of customer perceptions as potential barriers to consolidation is the current backlash against Health Maintenance Organisations. As a result of consolidations in healthcare and the fallout on customers, big, economically efficient firms are perceived as cold and impersonal. These issues must be overcome for consolidation to succeed. With competitors, the consolidator will face two issues. First, will the competitive response be strong?

While this might seem unlikely in a fragmented industry, there may be underlying relationships or other factors that may be exploited against the consolidator. Second, and possibly most important, will stiff competitive resistance force a consolidator to pay high premiums for acquisitions? This is certainly less preferred than consolidating an industry where businesses are more eager to sell. Quite simply, the higher the premium the consolidator is forced to pay, the harder it will be to eventually succeed in the industry.

Change Catalysts Favourable

Change catalysts can be both a positive and a negative issue for a consolidation play. In a positive light, change catalysts can alter a fragmented industry to enable successful consolidation. In the negative, change catalysts either prohibit successful consolidation or worse, disrupt a new or established consolidated industry. Regulatory issues and technological changes are the two most important factors in this variable. They are the primary change catalysts that can affect industries. Fragmented industries may have evolved under a particular regulatory or technological paradigm. When this paradigm shifts, with a new regulatory environment or a new technology, the industry may be immediately ripe for consolidation. Thus, the major questions for this variable are:

- Have change catalysts affected this industry?

- Are these change catalysts likely to further affect this industry?

- Does a consolidated firm stand to be affected negatively by new changes?

If the answer to all three questions is affirmative, then a consolidation play will likely be unsuccessful. The key here is that the industry should not be facing a tremendous amount of uncertainty in the future. While a catalyst may have created the opportunity for consolidation, the future industry should be relatively stable and free of major regulatory or technological factors.

A prime regulatory environment for consolidation may occur if there is no natural monopoly already and/or if there is one specific body that regulates the industry. In such a case, a consolidator can be assured that the likelihood of major change catalysts altering the industry is low. It is also useful to examine and understand the interaction between regulation and the fundamental economic forces that determine industry structure and would affect consolidation.

Currently, some of the major consolidation plays have arisen out of the change catalysts. The tower industry, for example, was extremely fragmented in the past. With the utility deregulation and the explosion of cellular services, the tower industry has been thrust into the limelight as a profitable consolidation play. However, as quickly as these catalysts can create a consolidation opportunity, they can spell doom for a consolidated industry.

Competitive Advantage Realizable for the Consolidator

Identification and full investigation of the first four primary variables are essential to this fifth variable. While the first four highlight the areas of concern that are not necessarily controllable by the consolidator, the fifth rest on the consolidator’s ability to implement successfully. Indeed, potential pitfalls raised among the first four issues may be addressed and overcome given complete analysis and proper implementation of the fifth variable.

The two primary competitive advantages for the consolidator are:

- The ability to exploit economies of scale and/or scope.

- The ability to leverage management talent.

These advantages are frequently cited in the popular literature today. The major issues that consolidators face, such as branding, tend to fall into one of these two buckets. Given that the nature of these advantages is well documented in strategy texts, we will not explain them in detail here. Suffice it to say that properly identifying and realizing these advantages may seem simpler in theory than in practice.

One particular example of successful execution is Wayne Huizenga. He created economies of scale through centralized purchasing and/ or management of assets. In the video rental business, he gained scale with Blockbuster to negotiate cheaper video purchase prices. In Waste Management’s trash and recycling services, he gained scale to enable cheaper management and maintenance of a trash hauler fleet.

Huizenga was able to leverage management by gobbling up mom-and-pop video stores and immediately converting them to the Blockbuster format with national management. Despite current analyst concerns for the companies, Huizenga’s consolidation plays were viewed as highly successful. Whether through an actual set of guidelines or just strong intuition, Huizenga has been able to identify potential industries where a consolidation play will work. More importantly, he has been able to implement their identified goals properly.

Success Requires Careful Implementation

Many agents have attempted consolidation over the past century of U.S. business. Some have been extraordinary successes, but some have failed. The new rise in attempted consolidation points to an even greater need for a systematic approach to developing consolidation strategies.

The 5 C’s framework should be used for identifying and analyzing fragmented industries where a consolidation play will likely be profitable. It is meant as a guide and tool to structure what is currently intuition and loose guidelines in most minds. The 5 C’s framework is a systematic structure in which to answer the following fundamental questions:

- Why is this industry fragmented?

- What are the opportunities and issues that must be addressed?

- Who are the industry stakeholders that consolidation will affect?

- Where are the obstacles to a consolidation play?

- How can this consolidation best be implemented with these issues in mind?

As stated previously, implementation will be the key to eventual success regardless of the obstacles or opportunities identified by the framework. Despite the level of industry attractiveness, individual success is highly dependent on the approach and persistence of the consolidator. Beyond implementation, a final issue remains.

How do you continue to succeed and grow beyond initial industry consolidation? This question is certainly beyond the scope of this framework but bears mentioning nonetheless. Slow growth and few opportunities may still characterize fragmented industries where a consolidation play will work. Huizenga has been criticized for bailing out on his ventures when the growth of the consolidated company was slowing.

Business Ethics

(Click on Topic to Read)

- What is Ethics?

- What is Business Ethics?

- Values, Norms, Beliefs and Standards in Business Ethics

- Indian Ethos in Management

- Ethical Issues in Marketing

- Ethical Issues in HRM

- Ethical Issues in IT

- Ethical Issues in Production and Operations Management

- Ethical Issues in Finance and Accounting

- What is Corporate Governance?

- What is Ownership Concentration?

- What is Ownership Composition?

- Types of Companies in India

- Internal Corporate Governance

- External Corporate Governance

- Corporate Governance in India

- What is Enterprise Risk Management (ERM)?

- What is Assessment of Risk?

- What is Risk Register?

- Risk Management Committee

Corporate social responsibility (CSR)

Lean Six Sigma

- Project Decomposition in Six Sigma

- Critical to Quality (CTQ) Six Sigma

- Process Mapping Six Sigma

- Flowchart and SIPOC

- Gage Repeatability and Reproducibility

- Statistical Diagram

- Lean Techniques for Optimisation Flow

- Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (FMEA)

- What is Process Audits?

- Six Sigma Implementation at Ford

- IBM Uses Six Sigma to Drive Behaviour Change

Research Methodology

Management

Operations Research

Operation Management

- What is Strategy?

- What is Operations Strategy?

- Operations Competitive Dimensions

- Operations Strategy Formulation Process

- What is Strategic Fit?

- Strategic Design Process

- Focused Operations Strategy

- Corporate Level Strategy

- Expansion Strategies

- Stability Strategies

- Retrenchment Strategies

- Competitive Advantage

- Strategic Choice and Strategic Alternatives

- What is Production Process?

- What is Process Technology?

- What is Process Improvement?

- Strategic Capacity Management

- Production and Logistics Strategy

- Taxonomy of Supply Chain Strategies

- Factors Considered in Supply Chain Planning

- Operational and Strategic Issues in Global Logistics

- Logistics Outsourcing Strategy

- What is Supply Chain Mapping?

- Supply Chain Process Restructuring

- Points of Differentiation

- Re-engineering Improvement in SCM

- What is Supply Chain Drivers?

- Supply Chain Operations Reference (SCOR) Model

- Customer Service and Cost Trade Off

- Internal and External Performance Measures

- Linking Supply Chain and Business Performance

- Netflix’s Niche Focused Strategy

- Disney and Pixar Merger

- Process Planning at Mcdonald’s

Service Operations Management

Procurement Management

- What is Procurement Management?

- Procurement Negotiation

- Types of Requisition

- RFX in Procurement

- What is Purchasing Cycle?

- Vendor Managed Inventory

- Internal Conflict During Purchasing Operation

- Spend Analysis in Procurement

- Sourcing in Procurement

- Supplier Evaluation and Selection in Procurement

- Blacklisting of Suppliers in Procurement

- Total Cost of Ownership in Procurement

- Incoterms in Procurement

- Documents Used in International Procurement

- Transportation and Logistics Strategy

- What is Capital Equipment?

- Procurement Process of Capital Equipment

- Acquisition of Technology in Procurement

- What is E-Procurement?

- E-marketplace and Online Catalogues

- Fixed Price and Cost Reimbursement Contracts

- Contract Cancellation in Procurement

- Ethics in Procurement

- Legal Aspects of Procurement

- Global Sourcing in Procurement

- Intermediaries and Countertrade in Procurement

Strategic Management

- What is Strategic Management?

- What is Value Chain Analysis?

- Mission Statement

- Business Level Strategy

- What is SWOT Analysis?

- What is Competitive Advantage?

- What is Vision?

- What is Ansoff Matrix?

- Prahalad and Gary Hammel

- Strategic Management In Global Environment

- Competitor Analysis Framework

- Competitive Rivalry Analysis

- Competitive Dynamics

- What is Competitive Rivalry?

- Five Competitive Forces That Shape Strategy

- What is PESTLE Analysis?

- Fragmentation and Consolidation Of Industries

- What is Technology Life Cycle?

- What is Diversification Strategy?

- What is Corporate Restructuring Strategy?

- Resources and Capabilities of Organization

- Role of Leaders In Functional-Level Strategic Management

- Functional Structure In Functional Level Strategy Formulation

- Information And Control System

- What is Strategy Gap Analysis?

- Issues In Strategy Implementation

- Matrix Organizational Structure

- What is Strategic Management Process?

Supply Chain