Prahalad and Gary Hammel

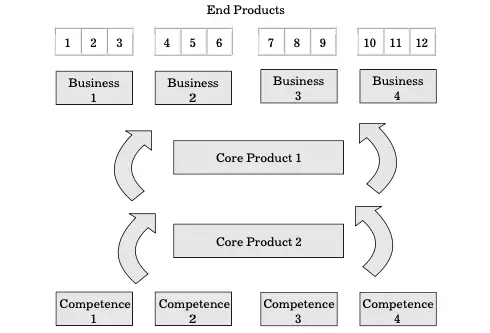

The core competencies are the source of competitive advantage and enable the firm to introduce various new products and services. According to Prahalad and Hammel, core competencies lead to the development of core products.

Core products are not directly sold to end users; rather, they are used to build many end-user products. For example, motors are a core product that can be used in a wide array of end products. The business units of the corporation each tap into the relatively few core products to develop a larger number of end-user products based on the core product technology. This flow from core competencies to end products as shown in fig.

Table of Content

The intersection of market opportunities with core competencies forms the basis for launching new businesses. By combining a set of core competencies in different ways and matching them to market opportunities, a corporation can launch a vast array of businesses.

Without core competencies, a large corporation is just a collection of discrete businesses. Core competencies serve as the glue that bonds the business units together into a coherent portfolio.

Developing Core Competencies

According to Prahalad and Hammel, core competencies arise from the integration of multiple technologies and the coordination of diverse production skills. There are three tests useful for identifying core competence. A core competence should:

- provide access to a wide variety of markets,

- contribute significantly to the end-product benefits,

- and be difficult for competitors to imitate.

Core competencies tend to be rooted in the ability to integrate and coordinate various groups in the organization. While a company may be able to hire a team of brilliant scientists in a particular technology, in doing so it does not automatically gain a core competence in that technology. It is the effective coordination among all the groups involved in bringing a product to market that results in core competence.

It is not necessarily an expensive undertaking to develop core competencies. The missing pieces of a core competency often can be acquired at a low cost through alliances and licensing agreements. In many cases, an organizational design that facilitates sharing of competencies can result in much more effective utilization of those competencies for little or no additional cost.

To better understand how to develop core competencies, it is worthwhile to understand what they do not entail. According to Prahalad and Hammel, core competencies are not necessarily about:

- Outspending rivals on R&D

- Sharing costs among business units

- Integrating vertically

While the building of core competencies may be facilitated by some of these actions, by themselves they are insufficient.

Loss of Core Competencies

Cost-cutting moves sometimes destroy the ability to build core competencies. For example, decentralization makes it more difficult to build core competencies because autonomous groups rely on outsourcing critical tasks, and this outsourcing prevents the firm from developing core competencies in those tasks since it no longer consolidates the know-how that is spread throughout the company.

Failure to recognize core competencies may lead to decisions that result in their loss. For example, in the 1970s many U.S. manufacturers divested themselves of their television manufacturing businesses, reasoning that the industry was mature and that high-quality, low-cost models were available from Far East manufacturers. In the process, they lost their core competence in the video, and this loss resulted in a handicap in the newer digital television industry.

Similarly, Motorola divested itself of its semiconductor DRAM business at the 256Kb level and then could not enter the 1Mb market on its own. By recognizing its core competencies and understanding the time required to build them or regain them, a company can make better divestment decisions.

Core Products

Core competencies manifest themselves in core products that serve as a link between the competencies and end products. Core products enable value creation in the end products. Examples of firms and some of their core products include:

- 3M – substrates, coatings, and adhesives

- Black & Decker – small electric motors

- Canon – laser printer sub-systems

- Matsushita – VCR sub-systems, compressors

- NEC – semi-conductors

- Honda – gasoline-powered engines

The core products are used to launch a variety of end products. For example, Honda uses its engines in automobiles, motorcycles, lawnmowers, and portable generators.

Because firms may sell their core products to other firms that use them as the basis for end-user products, traditional measures of brand market share are insufficient for evaluating the success of core competencies. Prahalad and Hammel suggest that core product share is the appropriate metric.

While a company may have a low brand share, it may have a high core product share and it is this share that is important from a core competency standpoint. Once a firm has successful core products, it can expand the number of uses to gain a cost advantage via economies of scale and economies of scope.

Implications for Corporate Management

Prahalad and Hammel suggest that a corporation should be organized into a portfolio of core competencies rather than a portfolio of independent business units. Business unit managers tend to focus on getting immediate end-products to market rapidly and usually do not feel responsible for developing company-wide core competencies.

Consequently, without the incentive and direction from corporate management to do otherwise, strategic business units are inclined to under-invest in the building of core competencies.

If a business unit does manage to develop its core competencies over time, due to its autonomy it may not share them with other business units. As a solution to this problem, Prahalad and Hammel suggest that corporate managers should have the ability to allocate not only cash but also core competencies among business units. Business units that lose key employees for the sake of a corporate core competency should be recognized for their contribution.

Competing for Future

Hamel and Prahalad start their most popular work, Competing for the Future, with some questions. “Does the senior management have a clear and broadly shared understanding of how the industry may be different ten years future?” “Is the task of regenerating core strategies receiving as much top management attention as the task of reengineering core process?”

They indicate, by those questions, how largely senior managements of corporations devote their efforts to maintain and improve only present business, such as restructuring and reengineering. The book, then, shows the limits of those actions for future success.

Hammel and Prahalad accomplished their theories in this masterpiece. The pair says management executives should act differently from others so that they could make their new future, which represents a new industry, new value, and new market; rather than maintaining or improving the present market or present product.

It can be, they say, first of all, having a good ‘Foresight,’ secondly, designing a ‘Strategic architecture’; and finally creating ‘Strategic intent’ and rebuilding ‘Core competencies’, which will pull a corporation to the future, is shown diagrammatically.

Foresight

For competing for tomorrow, Hammel and Prahalad insist that the first thing that should be done is to develop foresight. Foresight is prescience about the size and shape of tomorrow’s opportunities, such as new types of customer benefits or new ways of delivering the benefits. They explain forgetting the present market, the present product, the present business units, or the organization.

For instance, “Motorola dreams of a world in which telephone numbers will be assigned to people, rather than places; where small hand-held devices will allow people to stay in touch no matter where they are; and where the new communicators can deliver video images and data as well as voice signals.”

Strategic Architecture

To bring a corporation to a real future from foresight, the two theorists say it is the next action that should be done to craft a ‘Strategic Architecture’ instead of strategic planning. Strategic architecture should describe “which new benefits, or ‘functionalities’ (not present product) will be offered” for the future, “what new competencies will be needed to create those benefits,” and “how the customer interface will need to change to allow customers to access those benefits most effectively”.

They also indicate it is impossible to create a detailed plan for a ten-or fifteen-year competition, which is traditionally considered in strategic planning. They cite NEC, a Japanese electronic company, as an example of strategic architecture. NEC, initially a supplier of telecommunications equipment, dreamed of being a leader in ‘C&C,’ computers, and communication in the 1980s. The company identified three streams of technological and market evolution.

- Computing would evolve from large mainframes to distributed processing (now called “client-server”)

- Components would evolve from simple Integrated Circuits (ICs) to ultra-large-scale ICs

- Communications would evolve from mechanical cross-bar switching to complex digital systems.

Strategic Intent and Core Competence

The two gurus describe how to achieve the future by creating ‘strategic intent’ and rebuilding ‘core competencies’, which had been developed in their works before the book.

Strategic intent is something “ambitious and compelling” that “provides the emotional and intellectual energy” for the future. They explain “Strategic architecture is the brain; strategic intent is the heart.” They insist the most actually providing gateway to the future is “core competence.” Competencies are the integration of skills and technology, they defined.

Competencies of a corporation can be ‘core,’ which provide value to customers, are different from competitors, and are extendable in new products or services. To get to the future, core competencies should be founded, rebuilt, and developed. Motorola found, rebuilt, and developed its competencies in digital compression, flat screen displays, and battery technology, and the company made its foresight to the real future.

Business Ethics

(Click on Topic to Read)

- What is Ethics?

- What is Business Ethics?

- Values, Norms, Beliefs and Standards in Business Ethics

- Indian Ethos in Management

- Ethical Issues in Marketing

- Ethical Issues in HRM

- Ethical Issues in IT

- Ethical Issues in Production and Operations Management

- Ethical Issues in Finance and Accounting

- What is Corporate Governance?

- What is Ownership Concentration?

- What is Ownership Composition?

- Types of Companies in India

- Internal Corporate Governance

- External Corporate Governance

- Corporate Governance in India

- What is Enterprise Risk Management (ERM)?

- What is Assessment of Risk?

- What is Risk Register?

- Risk Management Committee

Corporate social responsibility (CSR)

Lean Six Sigma

- Project Decomposition in Six Sigma

- Critical to Quality (CTQ) Six Sigma

- Process Mapping Six Sigma

- Flowchart and SIPOC

- Gage Repeatability and Reproducibility

- Statistical Diagram

- Lean Techniques for Optimisation Flow

- Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (FMEA)

- What is Process Audits?

- Six Sigma Implementation at Ford

- IBM Uses Six Sigma to Drive Behaviour Change

Research Methodology

Management

Operations Research

Operation Management

- What is Strategy?

- What is Operations Strategy?

- Operations Competitive Dimensions

- Operations Strategy Formulation Process

- What is Strategic Fit?

- Strategic Design Process

- Focused Operations Strategy

- Corporate Level Strategy

- Expansion Strategies

- Stability Strategies

- Retrenchment Strategies

- Competitive Advantage

- Strategic Choice and Strategic Alternatives

- What is Production Process?

- What is Process Technology?

- What is Process Improvement?

- Strategic Capacity Management

- Production and Logistics Strategy

- Taxonomy of Supply Chain Strategies

- Factors Considered in Supply Chain Planning

- Operational and Strategic Issues in Global Logistics

- Logistics Outsourcing Strategy

- What is Supply Chain Mapping?

- Supply Chain Process Restructuring

- Points of Differentiation

- Re-engineering Improvement in SCM

- What is Supply Chain Drivers?

- Supply Chain Operations Reference (SCOR) Model

- Customer Service and Cost Trade Off

- Internal and External Performance Measures

- Linking Supply Chain and Business Performance

- Netflix’s Niche Focused Strategy

- Disney and Pixar Merger

- Process Planning at Mcdonald’s

Service Operations Management

Procurement Management

- What is Procurement Management?

- Procurement Negotiation

- Types of Requisition

- RFX in Procurement

- What is Purchasing Cycle?

- Vendor Managed Inventory

- Internal Conflict During Purchasing Operation

- Spend Analysis in Procurement

- Sourcing in Procurement

- Supplier Evaluation and Selection in Procurement

- Blacklisting of Suppliers in Procurement

- Total Cost of Ownership in Procurement

- Incoterms in Procurement

- Documents Used in International Procurement

- Transportation and Logistics Strategy

- What is Capital Equipment?

- Procurement Process of Capital Equipment

- Acquisition of Technology in Procurement

- What is E-Procurement?

- E-marketplace and Online Catalogues

- Fixed Price and Cost Reimbursement Contracts

- Contract Cancellation in Procurement

- Ethics in Procurement

- Legal Aspects of Procurement

- Global Sourcing in Procurement

- Intermediaries and Countertrade in Procurement

Strategic Management

- What is Strategic Management?

- What is Value Chain Analysis?

- Mission Statement

- Business Level Strategy

- What is SWOT Analysis?

- What is Competitive Advantage?

- What is Vision?

- What is Ansoff Matrix?

- Prahalad and Gary Hammel

- Strategic Management In Global Environment

- Competitor Analysis Framework

- Competitive Rivalry Analysis

- Competitive Dynamics

- What is Competitive Rivalry?

- Five Competitive Forces That Shape Strategy

- What is PESTLE Analysis?

- Fragmentation and Consolidation Of Industries

- What is Technology Life Cycle?

- What is Diversification Strategy?

- What is Corporate Restructuring Strategy?

- Resources and Capabilities of Organization

- Role of Leaders In Functional-Level Strategic Management

- Functional Structure In Functional Level Strategy Formulation

- Information And Control System

- What is Strategy Gap Analysis?

- Issues In Strategy Implementation

- Matrix Organizational Structure

- What is Strategic Management Process?

Supply Chain