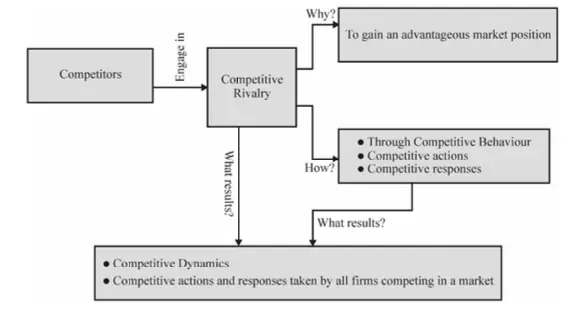

Whereas competitive rivalry concerns the ongoing actions and responses between a firm and its competitors for an advantageous market position, competitive dynamics concerns the ongoing actions and responses taking place among all firms competing within a market for advantageous positions.

To explain competitive rivalry, we described (a) factors that determine the degree to which firms are competitors (market commonality and resource similarity), (b) the drivers of competitive behavior for individual firms (awareness, motivation, and ability), and (c) factors affecting the likelihood a competitor will act or attack (first mover incentives, organizational size, and quality) and respond (type of competitive action, reputation, and market dependence). Building and sustaining competitive advantages are at the core of competitive rivalry, in that advantages are the link to an advantageous market position.

Table of Content

Competitive Dynamics

To explain competitive dynamics, we discuss the effects of varying rates of competitive speed in different markets (called slow-cycle, fast-cycle, and standard cycle markets) on the behavior (actions and responses) of all competitors within a given market. Competitive behaviors as well as the reasons or logic for taking them are similar within each market type but differ across market types.

Thus competitive dynamics differ in slow-cycle, fast-cycle, and standard-cycle markets. Thus sustainability of the firm’s competitive advantages is an important difference between the three market types.

As you know that firms want to sustain their advantages for as long as possible, although no advantage is permanently sustainable.

Slow-cycle Markets

Slow-cycle markets in which the firm’s competitive advantages are shielded from imitation for what are commonly long periods and where imitation is costly. Competitive advantages are sustainable in slow-cycle markets.

Building on of a kind competitive advantage that is proprietary leads to competitive success in a slow-cycle market. This type of advantage is difficult for competitors to understand and costly to imitate advantage results from unique historical conditions, causal ambiguity, and or social complexity. Copyrights, geography, patents, and ownership of information resources are examples of what leads to one kind of advantage.

Once a proprietary advantage is developed, the firm’s competitive behavior in a slow-cycle market is oriented to protecting, maintaining, and extending that advantage. Thus, the competitive dynamics in slow-cycle markets involve all firms concentrating on competitive actions and responses that enable them to protect, maintain, and extend their proprietary competitive advantage.

Fast-cycle Markets

Fast-cycle markets are markets in which the firm’s capabilities that contribute to competitive advantages aren’t shielded from imitation and where imitation is often rapid and inexpensive. Thus, competitive advantages aren’t sustainable in fast-cycle markets. Firms competing in fast-cycle markets recognize the importance of speed; these companies appreciate that time is as precious a business resource as money or headcount – and that the costs of hesitation and delay are just as steep as going over budget or missing a financial forecast.

Such high-velocity environments place considerable pressure on top managers to make strategic decisions quickly, but they must be effective. The often substantial competition and technology-based strategic focus make strategic decisions complex, increasing the need for a comprehensive approach integrated with decision speed, two often-conflicting characteristics of the strategic decision process.

Reverse engineering and the rate of technology diffusion in fast-cycle markets facilitate rapid imitation. A competitor uses reverse engineering to quickly gain the knowledge required to imitate or improve the firm’s products, usually in only a few months. Technology is diffused rapidly in fast-cycle markets, making it available to competitors in a short period. The technology often used by fast-cycle competitors isn’t proprietary, nor is it protected by patents, as in slow-cycle markets.

Fast-cycle markets are more volatile than slow-cycle markets and standard-cycle markets. Indeed, the pace of competition in fast-cycle markets is almost frenzied, as companies rely on ideas and the innovations resulting from them as the engines of their growth. Because prices fall quickly in these markets, companies need to profit quickly from their product innovations. Fast-cycle market characteristics make it virtually impossible for companies in this type of market to develop sustainable competitive advantages.

Recognizing this, firms avoid “loyalty” to any of their products, preferring to cannibalize their current product by launching a new product before competitors learn how to do so through successful imitation. This emphasis creates competitive dynamics that differ substantially from those in slow-cycle markets.

Instead of concentrating on protecting, maintaining, and extending competitive advantages, as is the case for firms in slow-cycle markets, companies competing in fast-cycle markets focus on learning how to rapidly and continuously develop new competitive advantages that are superior to those they replace. In fast-cycle markets, firms don’t concentrate on trying to protect a given competitive advantage because they understand that the advantage won’t exist long enough to extend it.

Competitive dynamics in this market type find firms taking actions and responses in the course of competitive rivalry that is oriented to rapid and continuous product introductions and the use of a stream of ever-changing competitive advantages. The firm launches a product as a competitive action and then exploits the advantage associated with it for as long as possible.

However, the firm also tries to move to another temporary competitive action before competitors can respond to the first one. Thus, competitive dynamics in fast-cycle markets, in which all firms seek to achieve new competitive advantages before competitors, learn how to effectively respond to current ones, often result in rapid product upgrades as well as quick product innovations.

As our discussion suggests, innovation has a dominant effect on competitive dynamics in fast-cycle markets. For individual firms, this means that innovation is a key source of competitive advantage. Through innovation, the firm can cannibalize its products before competitors successfully imitate them.

Standard-cycle Markets

Standard-cycle markets are those in which the firm’s competitive advantages are moderately shielded from imitation and where imitation is moderately costly. Competitive advantages are partially sustainable in standard-cycle markets, but only when the firm can continuously upgrade the quality of its competitive advantages. The competitive actions and responses that form a standard-cycle market’s competitive dynamics find firms seeking large market shares, trying to gain customer loyalty through brand names, and carefully controlling their operations to consistently provide the same positive experience for customers.

Companies competing in standard-cycle markets serve many customers. Because the capabilities on which their competitive advantages are based are less specialized, imitation is faster and less costly for standard-cycle firms than for those competing in slow-cycle markets. However, imitation is less quick and more expensive in these markets than in fast-cycle markets.

Thus, the competitive dynamics in standard-cycle markets rest midway between the characteristics of dynamics in slow-cycle and fast-cycle markets. The quickness of imitation is reduced and becomes more expensive for standard-cycle competitors when a firm can develop economies of scale by combining coordinated and integrated design and manufacturing processes with a large sales volume.

Because of large volumes, the size of mass markets, and the need to develop scale economies, the competition for market share is intense in standard-cycle markets. This form of competition is readily evident in the battles between Coca-Cola and PepsiCo.

Business Ethics

(Click on Topic to Read)

- What is Ethics?

- What is Business Ethics?

- Values, Norms, Beliefs and Standards in Business Ethics

- Indian Ethos in Management

- Ethical Issues in Marketing

- Ethical Issues in HRM

- Ethical Issues in IT

- Ethical Issues in Production and Operations Management

- Ethical Issues in Finance and Accounting

- What is Corporate Governance?

- What is Ownership Concentration?

- What is Ownership Composition?

- Types of Companies in India

- Internal Corporate Governance

- External Corporate Governance

- Corporate Governance in India

- What is Enterprise Risk Management (ERM)?

- What is Assessment of Risk?

- What is Risk Register?

- Risk Management Committee

Corporate social responsibility (CSR)

Lean Six Sigma

- Project Decomposition in Six Sigma

- Critical to Quality (CTQ) Six Sigma

- Process Mapping Six Sigma

- Flowchart and SIPOC

- Gage Repeatability and Reproducibility

- Statistical Diagram

- Lean Techniques for Optimisation Flow

- Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (FMEA)

- What is Process Audits?

- Six Sigma Implementation at Ford

- IBM Uses Six Sigma to Drive Behaviour Change

Research Methodology

Management

Operations Research

Operation Management

- What is Strategy?

- What is Operations Strategy?

- Operations Competitive Dimensions

- Operations Strategy Formulation Process

- What is Strategic Fit?

- Strategic Design Process

- Focused Operations Strategy

- Corporate Level Strategy

- Expansion Strategies

- Stability Strategies

- Retrenchment Strategies

- Competitive Advantage

- Strategic Choice and Strategic Alternatives

- What is Production Process?

- What is Process Technology?

- What is Process Improvement?

- Strategic Capacity Management

- Production and Logistics Strategy

- Taxonomy of Supply Chain Strategies

- Factors Considered in Supply Chain Planning

- Operational and Strategic Issues in Global Logistics

- Logistics Outsourcing Strategy

- What is Supply Chain Mapping?

- Supply Chain Process Restructuring

- Points of Differentiation

- Re-engineering Improvement in SCM

- What is Supply Chain Drivers?

- Supply Chain Operations Reference (SCOR) Model

- Customer Service and Cost Trade Off

- Internal and External Performance Measures

- Linking Supply Chain and Business Performance

- Netflix’s Niche Focused Strategy

- Disney and Pixar Merger

- Process Planning at Mcdonald’s

Service Operations Management

Procurement Management

- What is Procurement Management?

- Procurement Negotiation

- Types of Requisition

- RFX in Procurement

- What is Purchasing Cycle?

- Vendor Managed Inventory

- Internal Conflict During Purchasing Operation

- Spend Analysis in Procurement

- Sourcing in Procurement

- Supplier Evaluation and Selection in Procurement

- Blacklisting of Suppliers in Procurement

- Total Cost of Ownership in Procurement

- Incoterms in Procurement

- Documents Used in International Procurement

- Transportation and Logistics Strategy

- What is Capital Equipment?

- Procurement Process of Capital Equipment

- Acquisition of Technology in Procurement

- What is E-Procurement?

- E-marketplace and Online Catalogues

- Fixed Price and Cost Reimbursement Contracts

- Contract Cancellation in Procurement

- Ethics in Procurement

- Legal Aspects of Procurement

- Global Sourcing in Procurement

- Intermediaries and Countertrade in Procurement

Strategic Management

- What is Strategic Management?

- What is Value Chain Analysis?

- Mission Statement

- Business Level Strategy

- What is SWOT Analysis?

- What is Competitive Advantage?

- What is Vision?

- What is Ansoff Matrix?

- Prahalad and Gary Hammel

- Strategic Management In Global Environment

- Competitor Analysis Framework

- Competitive Rivalry Analysis

- Competitive Dynamics

- What is Competitive Rivalry?

- Five Competitive Forces That Shape Strategy

- What is PESTLE Analysis?

- Fragmentation and Consolidation Of Industries

- What is Technology Life Cycle?

- What is Diversification Strategy?

- What is Corporate Restructuring Strategy?

- Resources and Capabilities of Organization

- Role of Leaders In Functional-Level Strategic Management

- Functional Structure In Functional Level Strategy Formulation

- Information And Control System

- What is Strategy Gap Analysis?

- Issues In Strategy Implementation

- Matrix Organizational Structure

- What is Strategic Management Process?

Supply Chain